В болница за услуги, Лахор, екипът за инсулт носи торба с всичко необходимо за лечение на пациент с остър исхемичен инсулт – от IV канюли, глюкомер и спринцовки до епруветки, памучни тампони и лента. Също така в чантата има смартфон, който може да предава КТ изображения с висока разделителна способност чрез WhatsApp. Смартфонът е подарък от донор. Малките неща са от значение.

Канапсакът, както и телефонът, е решение – част от изобретателност за преодоляване на ограниченията на ресурсите. Той решава най-малко някои от проблемите, които срещате при лечение на инсулт в спешно отделение, което приема над хиляда пациенти на ден. Конкуренцията за легла е интензивна и

Както в голяма част от системата на общественото здравеопазване в Пакистан, болницата е с недостатъчен персонал. Поради тази причина, жителите остават в спешното отделение, за да наблюдават и да се грижат за пациенти с инсулт, получаващи тромболиза. И когато свършат с медицинската сестра, същите млади лекари стават портиери, закарвайки пациентите си в отделението по неврология, разположено на четвъртия етаж на различна сграда.

Това е интелигентна хакерска атака: отдадеността на ново поколение от резиденти по неврология, които моделират поведението си по примера, даден от лекар, чиято кампания за промяна на грижите при инсулт в Лахор най-накрая дава плод.

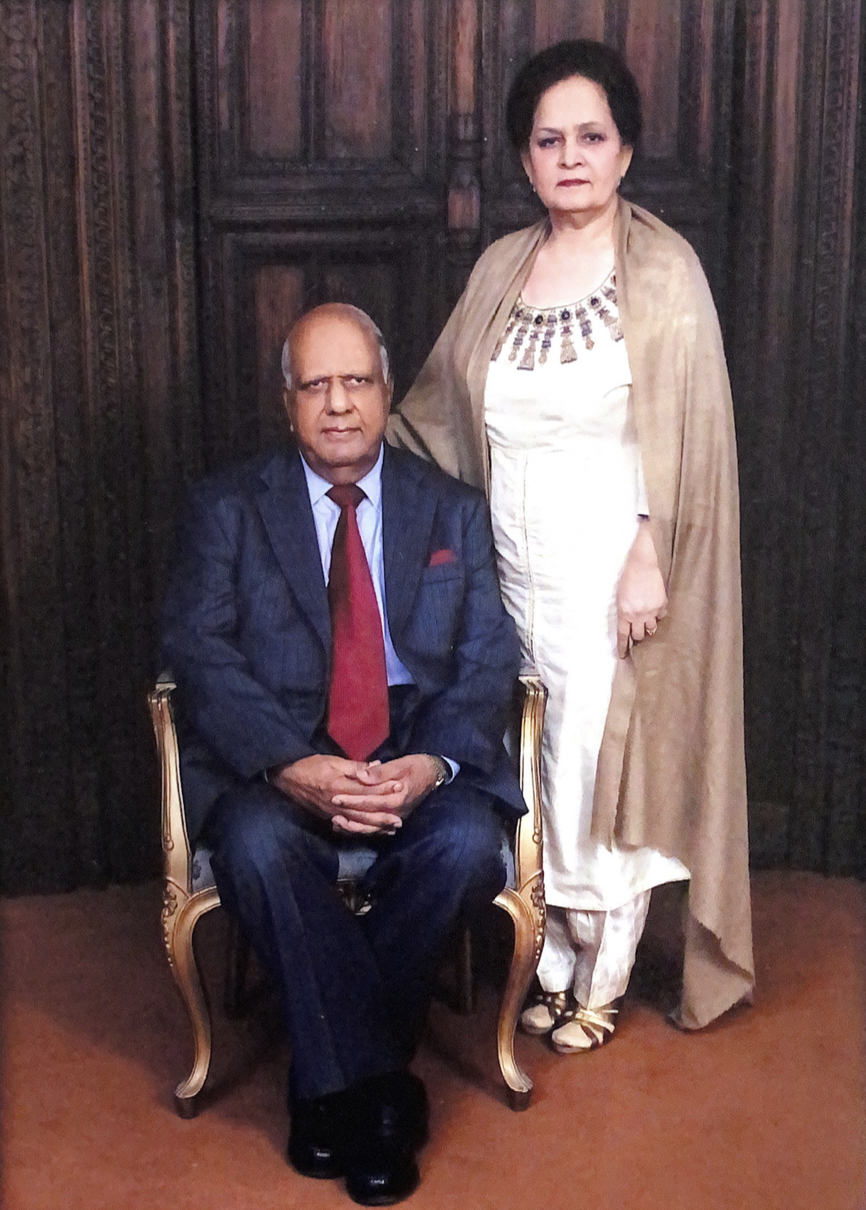

DR QASIM Bashir е отгледан в неврохирургия по начина, по който децата на спортните герои растат до терена. Покойният му баща, професор Башир Ахмед, е пионер в неврохирургията в Пакистан и през 1964 г. основава отделение по неврохирургия в болница Lahore General Hospital, което по-късно става известен институт по невронауки Punjab (PINS).

Всички братя и сестри Башир последваха легендарния си баща в медицината, посещавайки Медицинския колеж „Крал Едуард“ в Лахор, преди да продължат обучението си в чужбина. Д-р Касим описва стипендията си по невроендоваскуларна хирургия в Университета на Илинойс като „повратна точка“.

„До 1998 г. бях виждал само неврохирургия; след това осъзнах потенциала на минимално инвазивните лечения за неврологични заболявания, включително инсулт.“

През 2012 г. д-р Касим Башир се завръща в Пакистан, който по онова време е една от малкото държави, които все още не са одобрили rTPA за лечение на остър исхемичен инсулт. Дори преди лекарство да бъде одобрено от официалния регулаторен орган лекарство в Пакистан [DRAP], той получава специален институционален отказ от DRAP, за да започне да предлага rTPA в Института за услуги

на свързаната с медицинските науки болница през 2021 г.

Осъзнавайки, че търсенето на финансиране от правителството ще бъде дълъг и досаден процес, д-р Касим се свързва с американския филантроп от пакистански произход г-н Ашер Азиз, който дава 100 000 долара в чест на покойната си майка г-жа Нисар Азиз, която е била жертва на инсулт. Безвъзмездната помощ улесни специална и самостоятелна програма за остър инсулт в публичния сектор в град Лахор. Всъщност, казва д-р Касим, „това финансиране постави самата основа за лечение на остър инсулт в публичния сектор на национално ниво“.

Безвъзмездната помощ предостави безплатен достъп до тромболиза за бедни пациенти с остър исхемичен инсулт в болница за услуги за третични грижи с 1650 легла. Помощта идва от много други източници, казва д-р Касим. „Асоциацията на лекарите на пакистанското спускане на Северна Америка (APPNA), здравният отделение на Пенджаб, DRAP, пакистанската митническа власт и Boehringer Ingelheim, както и администрациите на Болницата за услуги и Института за услуги на медицинските науки, бяха сред тези, които се възползваха от услугите си за благородната кауза.“

В рамките на 20 месеца екипът за лечение на инсулт в болница за услуги лекува повече от 60 пациенти с остър инсулт с тромболиза, не среща усложнения, свързани с лекарство, и вижда положителни резултати след три месеца. Времето от вратата до иглата не е далеч от международния стандарт, а изследователската работа на техния отделение от жители на неврологията е призната с отличие на годишните конференции на Пакистанското дружество по неврология и Пакистанското дружество по инсулт.

Всичко това има значение, но особено това: Да имаш властта да лекуваш бедния пациент безплатно и да станеш свидетел на възстановяването му е „невероятно“, казва д-р Касим. „То носи сълзи на очите ти.“ Това е и движещата сила за разширяване на услугите за инсулт, достъпни за 13-милионното население на Лахор.

Филантропията може да ви накара да започнете, но не може да ви поддържа, казва д-р Касим. След като можете да покажете, че вашата програма е успешна, трябва да включите публичния сектор за неговата дългосрочна непрекъснатост.

Планът за разширяване на д-р Касим включва център и модел на спици, който се върти около най-големия неврохирургичен център в Пакистан – този, създаден от баща му. Той е зает от няколко месеца с реформиране на невроендоваскуларната програма в PINS и разработване на невроваскуларна услуга, така че пациентите с оклузия на голям съд или тези, които не са пригодни за тромболиза, да могат да бъдат насочени за тромбектомия.

В Болницата за услуги също има напредък. Най-накрая има специализиран залив за инсулти с четири легла на входа на нововъзстановеното спешно отделение. Има специализирани лекари и медицински сестри, които са се възползвали от онлайн обучението в академията „Ангели“ и използват нейните онлайн ресурси изключително.

Налице е процъфтяваща култура на мониторинг на качеството; екипът представя своите случаи на RES-Q и има причина да очаква с нетърпение първата си награда на WSO „Ангели“. Те могат също така да гледат напред към укрепване на линията благодарение на финансирана от донора програма за стипендия, в която всяка година ще се обучават един невролог по инсулт, един неврохирург и една медицинска сестра по инсулт в PINS.

Ако нещо е по-неотложно от обучението на невролози, то учи обществеността за симптомите на инсулт и болниците, готови за инсулт, смята д-р Касим. Не само поради очевидната причина, че повече пациенти ще имат достъп до лечение навреме, но и защото той се доверява на образована общественост, за да окаже така необходимия натиск върху системата на здравеопазването, като изисква най-доброто лечение. Много, много по-надолу в списъка се присъединява към стремежа към сертифициране на центъра за инсулт, който в момента се провежда в региона с цел стандартизиране на лечението на инсулт.

„Нашият приоритет е прилагането и прилагането на институционални протоколи в нашите болници и превръщането им в модели за подражание в Лахор, където имаме огромно население, за което да се грижим“, казва той.

„Ако се посветим на тази цел, няма да се провалим.“